A structure that is smaller than the wavelength of visible light (390-770 nanometers) should not really be able to scatter light. But that is exactly what the new nanoantenna does. The trick employed by the Chalmers researchers is to build an antenna with an asymmetric material composition, creating optical phase shifts.

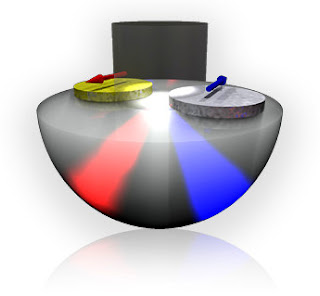

The antenna consists of two nanoparticles about 20 nanometers apart on a glass surface, one of silver and one of gold. Experiments show that the antenna scatters visible light so that red and blue colours are directed in opposite directions.

“The explanation for this exotic phenomenon is optical phase shifts,†says Timur Shegai, one of the researchers behind the discovery. “The reason is that nanoparticles of gold and silver have different optical properties, in particular different plasmon resonances. Plasmon resonance means that the free electrons of the nanoparticles oscillate strongly in pace with the frequency of the light, which in turn affects the light propagation even though the antenna is so small. “

The nanoantenna acts as a router for red and blue light, due to the nanoparticles of gold and silver having different optical properties. Image: Timur ShegaiThe method used by the Chalmers researchers to control the light by using asymmetric material composition â€" such as silver and gold â€" is completely new. It is easy to build this kind of nanoantenna; the researchers have shown that the antennas can be fabricated densely over large areas using cheap colloidal lithography.

The research field of nanoplasmonics is a rapidly growing area, and concerns controlling how visible light behaves at the nanoscale using a variety of metal nanostructures. Scientists now have a whole new parameter â€" asymmetric material composition â€" to explore in order to control the light.

Nanoplasmonics can be applied in a variety of areas, says Mikael Käll, professor in the research group at Chalmers.

“One example is optical sensors, where you can use plasmons to build sensors which are so sensitive that they can detect much lower concentrations of toxins or signalling substances than is possible today. This may involve the detection of single molecules in a sample, for example, to diagnose diseases at an early stage, which facilitates quick initiation of treatment.â€

The results were presented at an international conference on optical nanosensors at Chalmers this week. Chalmers is one of the leading universities in nanoplasmonic biosensors, and 130 scientists from around the world are attending the conference.

The research has received financial support from the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research, the Swedish Research Council and the Göran Gustafsson Foundation.

For more information, please contact: Timur Shegai, PhD, bionanophotonics, +46 31 772 31 23, timurs@chalmers.se Mikael Käll, Professor, bionanophotonics, +46 31 772 31 19, mikael.kall@chalmers.se

Contact: Christian Borg press@chalmers.se 46-317-723-395 Swedish Research Council